Death and the King’s Horseman was first published in 1975 by Nigerian playwright Wole Soyinka. Set in 1940s Yoruba, the play covers the cultural crash between British colonizers and native Nigerians. All while following the narrative of Elesin Oba; a Nigerian horseman who must commit ritual suicide to honor his king. Throughout the five act play, the Pilkings family, alongside other white colonizers, can be seen diminishing Nigerian culture. This is a central theme that serves as a catalyst for the entire play. For my unessay, I choose to portray artwork that showcases this suppression of culture based on dialogue within different acts. All of the artwork is split between light and dark paper. The darkness symbolizes the oppression of the bright Nigerian culture.

In act one, Elesin and his praise-singer discuss Elesin’s duty to die in the market as it’s closing. The praise-singer recounts all that their people and their city have survived throughout war and slavery. To Elesin, he states,

“PRAISE-SINGER: In their time the great wars came and went; the white slavers came and went, they took away the heart of our race, they bore away the mind and muscle of our race. The city fell and was rebuilt; the city fell and our people trudged through mountain and forest to found a new home but […] Our world was never wrenched from its true course.” (Soyinka, p. 10.)

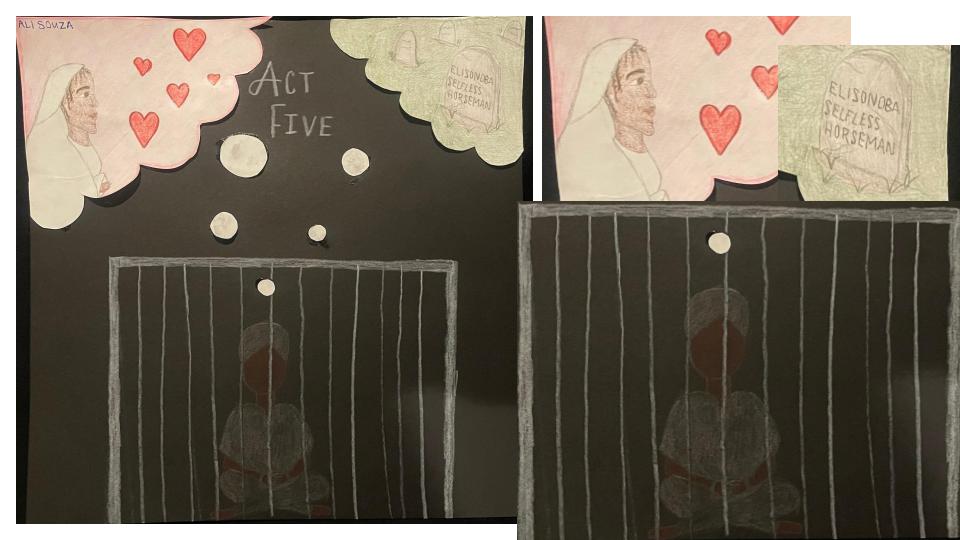

Considering these lines, I instantly saw a picture in my head. A Nigerian man climbing uphill in a bright city, with English colonizers doing everything they can to encapture him. Using Soyinka’s picture of war, mountains, and the city, I created this image:

Upon further research of Yoruban clothing within the time period, alongside viewing some costume designs from the Stratford Festival’s production of the play, I chose to portray the man in a Nigerian suit and turban. I wanted to showcase the heart of his culture being taken. To do this, I didn’t include faces or traditional patterns on his cloak. Amongst this, I wanted to include more detail from the quote, like the city burning to ash and .

Early in act two, Simon and Jane Pilkings are seen by Amusa disrespecting a traditional Nigerian practice: egungun. Their conversation goes as follows:

“AMUSA: Sir it is a matter of death. How can man talk against death to person in uniform of death? Is like talking against government to person in uniform of police. Please sir, I go and come back. […] I no touch the egungun. That egungun inself, I no touch. And I no abuse ‘am. I arrest ringleader but I treat egungun with respect.” (Soyinka, pp. 24-5.)

Amusa came to speak with Pilkings about Elesin’s intentions to commit suicide, but can not allow himself to mention death while Pilkings is dressed in the egungun. That is because the egungun masquerade is meant to honor dead Yoruba ancestors, and is believed that when one wears the egungun, their ancestor is able to portray through them. This ceremonial outfit was popular in the 1930s-’50s in Yoruba, Nigeria.

Although the Pilkings couple wears a different style of egungun in the play, I chose to draw a traditional style egungun. The style reveals itself as a large skirt, made up of cotton, velvet, wood and plastic belts that fully camouflage its wearer. In the middle of its beauty, lies a black triangle, showcasing their mockery of death, unable to truly look it in the eye, despite wearing an egungun.

The Pilkings couple wearing the egungun is disrespectful because of its deeper cultural meaning, but it’s even more disrespectful that the Pilkings family do not care about its meaning, and they wear it to mock their culture.

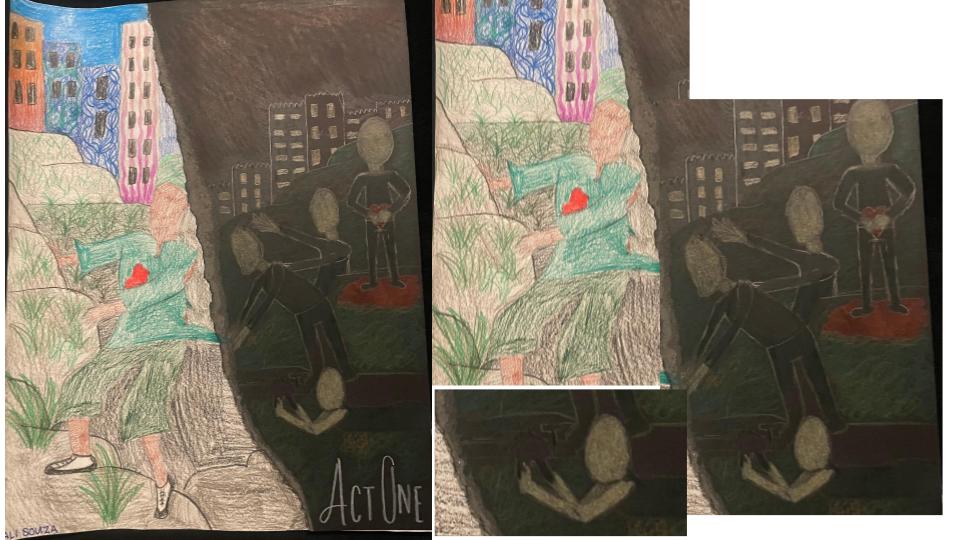

In act three, the Nigerian women are laughing at Amusa; openly judging him for obeying a white man, and mocking him for his job. After their long dialogue of banter, one of the women calls out “Sergeant!” This leads Amusa to snap to attention, and respond “Yessir!” out of muscle memory.

This moment in act three displays a suppression of culture because of the way Amusa is unable to converse freely with those of his same race. His job as a police officer isn’t what isolates him from his peers, but rather him working for a European colonizer that forces other Nigerians to dislike him.

In act four, the Pilkings attend a party in their egungun costumes. I chose to display the outfit I believe they are wearing in the scene:

Through further research, I discovered that it is frowned upon to show your face while wearing an egungun, because it is believed that one embodies their ancestor while in the suit. The Pilkings mock their culture by (not only wearing it in the first place) removing their masks and showing people their faces. The black box with the eyes is supposed to represent this disrespect.

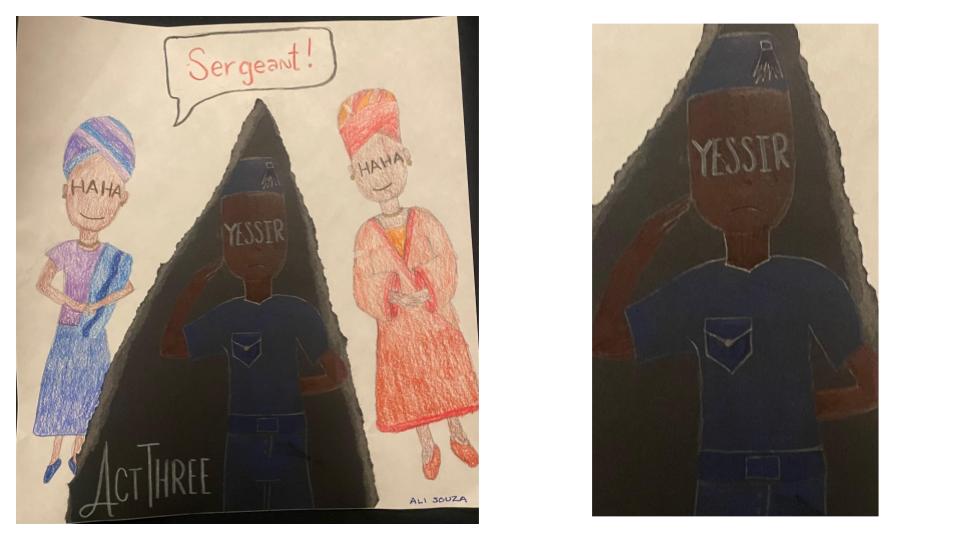

Lastly, for act five, I chose to show Elesin succumbed to the darkness, as he sits in his jail cell. Above him are two thought bubbles: one, his love and the other, his sacrificial death. They are meant to symbolize what he wants to do for himself and for his culture: