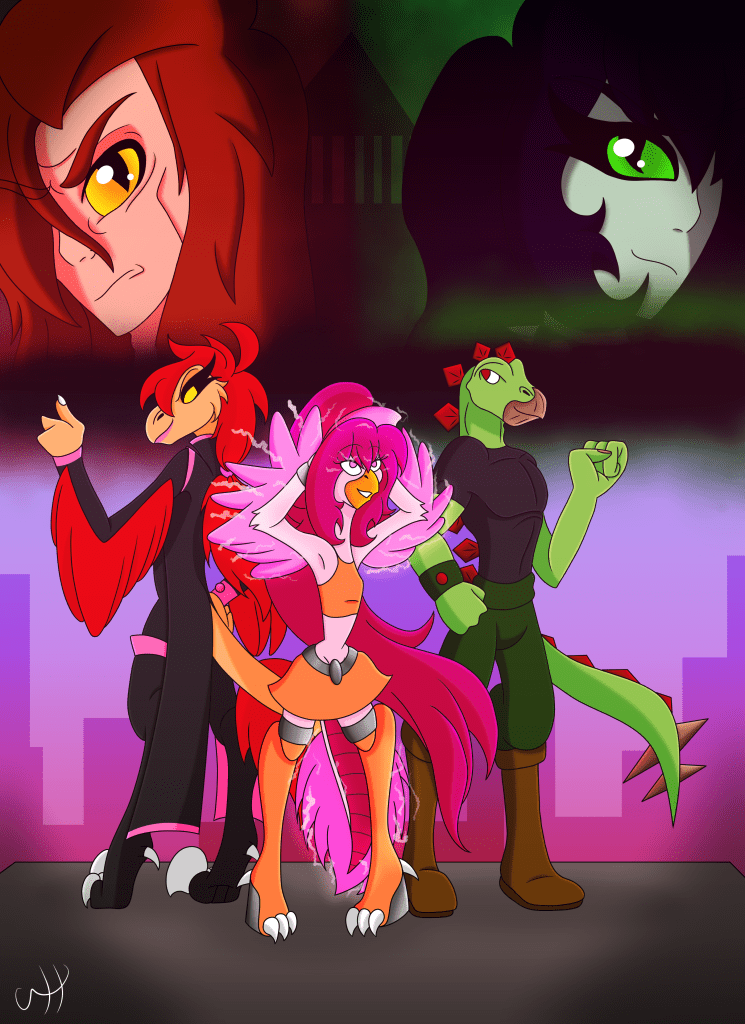

*All art presented, traditional and digital, was made by Sara Howell*

Sara Howell

Nic Helms

Critical Theory

7 May 2024

Prehistoric Animals to Humanoids in Dinosaur Creek

Regarding anthropomorphic characters in fiction, we genuinely portray them as people in their world, like the animals in Disney’s Zootopia. “In the psychological literature, anthropomorphism has been defined as the human tendency to see human characteristics or mental states in nonhuman agents, either natural entities, objects or nonhuman animals, attributing them human intentions, motivations, goals or emotions” (Prato-Previde 1). But what happens when an anthropomorphic character starts as a regular animal living freely in the wild before becoming domesticated with human intelligence? Better yet, what if that animal was a prehistoric creature, from millions of years in the past WAY before humans existed? What if that particular animal was taken from their wild habitat, thrown into the 21st century, filled with human civilization, and genetically mutated to have the same upright posture, brain size, and ability to speak just like a human being while still retaining their animalistic features, such as head shapes, claws, and tails? That is exactly what the characters of Dinosaur Creek go through.

Dinosaur Creek follows a secret company called Terrarium, living in the 21st-century Anthropocene epoch. “In recognition of the immense human impact upon the Earth system, the term Anthropocene has come to the fore, with its proponents arguing that we are in a new, human-dominated geological epoch” (Sage 303). It specializes in using time travel technology to go back to the Mesozoic Era and capture feral dinosaurs, pterosaurs, and marine reptiles. Using mutagen and electric wavelengths, the animals are fitted into humanoid bodies. They are given expanded minds to think, speak, and express themselves just like humans, while still retaining their paleo features and memories of their feral lives. These humanoid paleo beings are appropriately named “Paleoids.” The principal story follows a cast of paleoids who rebel from Terrarium and navigate the 21st century with help from a few human allies. At the same time, they fight against forces of evil ranging from Terrarium’s Dinosaur Agents, rival rebellion groups hell-bent on destroying humanity, and secret sorcerors who unlock a magical power hidden within Earth’s secret history.

The story is based on the early 1980s and 90s cartoons such as Dinosaucers (1987) and Extreme Dinosaurs (1997) which follow similar concepts. Dinosaur Creek upgrades from those shows by acting as a continuing story implemented with adult themes, such as diversity, war, trauma, LGBT+ representation, coming of age, and playing God. “‘God put creatures on this planet for a reason, to live until the day they die, and thank the humans for proving Him wrong’” (Ch. 1). Perhaps the biggest theme being tackled within Dinosaur Creek is discovering self-identity; understanding the psychology these paleoids go through when they’re a wild feral animal from a different time turning into a human-like creature living in a new one drastically different from their natural environment. The main character, Tex the tyrannosaurus rex, represents this theme the most as he starts the story as a dinosaur going through Terrarium’s mutation and rehabilitation process.

From the beginning, Tex has his future planned out as a feral. He gates a female tyrannosaurus rex named Kireina, goes through the capture and mutation process, and learns how to navigate Terrarium with her. Once he becomes a paleoid, he is given the Terrarium run down of what he is now, what humans are, and Terrarium’s mission. He processes this while uncovering his new abilities, such as his increased intelligence and ability to speak. “‘Well…you pretty much got that right. Not to mention with these new bodies, our minds feel a bit bigger cause not only am I saying words I never knew existed but the fact that I’m saying them formally and properly’ the male rex awkwardly explained” (Ch. 1). Tex was used to communicating through smaller grunts and didn’t think as hard. But speaking out for the first time gives him a new challenge, one that he must adapt to without having a choice before. “This analogy can be limiting and misleading: for one thing, animals cannot speak for themselves in the kind of texts that constitute animals as objects of study. If animals cannot represent themselves in rational thought and as it is manifested in language, how can they be read or heard?” (McDonell 6). He spends a few weeks in Terrarium’s care before exploring the human city of Hell Creek for the first time. However, complications with learning about Terrarium, as well as Kireina gaining new, twisted ideas about humans, make Tex change everything. He breaks up with Kireina, allies with other dinosaurs he befriended, and leads an escape from the company (Ch. 6). All the while, he learns how to put others before himself, experiencing and learning new feelings that almost make him feel human.

Part of having this ability to access his mind’s capabilities also includes accessing emotional expressions. Animals have their unique ways of expressing feelings, but if that animal is given human expression, they have to adjust to accessing other emotions outside of the basics (happy, angry, sad, fear, etc.). An important emotion that paleoids like Tex have to learn is empathy. “Empathy is considered a fundamental component of human emotional experience with an essential role in human social life and interactions. It promotes social interactions, motivates prosocial behavior and caring for others (humans or nonhumans), inhibits aggression and is an affective/cognitive prerequisite for moral reasoning and behavior” (Prato-Previde 1). In Tex’s case, he learns to be empathetic to other species, especially after he tries to move on from being a predator who spent his feral life hunting other dinosaurs for food.

Learning empathy for others and using his given strength to protect others is Tex’s mission throughout the story. “Empathy, attachment and anthropomorphism are human psychological mechanisms that are considered relevant for positive and healthy relationships with animals, but when dysfunctional or pathological determine physical or psychological suffering, or both, in animals as occurs in animal hoarding” (Prato-Previde 1). Tex has to learn to put the past behind him and be a better person. However, he is constantly threatened by those who think T. rex are just predatory beasts who only eat others when given the opportunity. “Before, he was just a cold-blooded predator looking for a meal constantly. But now, he could do more and think about how he can make more happen” (Ch. 10).

Stereotyping his species as such leaves him with emotional pain and unlike his friends who figure out their personalities and their interests, Tex spends the story putting others’ needs before his own. “‘Before I was following the rules the wild wanted me to. But now I can think freely and decide I don’t want to live like a savage anymore. I’m willing to leave that gruesome life behind me and spend my life protecting those I care about and I’ll protect others along the way because it’s the right thing to do’” (Ch. 10). Although this gives him empathy for other, it also makes him feel his character is empty and without purpose.

Part 1, Chapter 10: Connect

*Note: The paleoid characters in the story have special morph bracelets that give them human disguises*

“Tex tried so many times to prove he could be someone better than his old self. Someone who could lead a team of dinosaurs to a free life and protect human life. Yet, he spent so much time putting others’ lives before his that he never got around to figuring himself out. What interest did he have that was plain and simple like his friends? What purpose did he think he could serve in this timeline that hasn’t been done before by other dinosaurs in the modern day?” (Ch. 20).

One of the biggest obstacles he encounters when learning this is his friend Emily Tops, a human police detective whom he befriends after she discovers his paleoid existence. Through her, he learns about how laws work and the importance of the justice system crafted by humans. “‘A rule, made by the government, the justice system. If anyone breaks those laws, we have to arrest them’ she clarified. ‘And who says those laws justify what’s right or wrong? Is it a system that the humans made or something? Tex asked, having doubts about the concept of humans deciding laws that separate people who do good and bad things” (Ch. 4). While he learns to respect these laws, Tex also forms an attachment to Emily that develops into romance. But of course, Tex knows a relationship between a human and a paleoid is unethical, despite proving he wants nothing more than to protect her.

Perhaps one of the biggest aspects of his character is moving on from romantic relationships and establishing new ones. At the start, he is the mate of Kireina. But when they explore the 21st-century city together, Kireina adapts ideas that are drastically different than his own. “‘Oh, please. Who says I have to? I’m not technically a legal citizen, nor am I a human to partake in these human cultures and rules. I’m a dinosaur, just like the rest of you, I should do things our own way, just as nature intended’ (Ch. 5). She doesn’t want to indulge in the human lifestyle and instead wants to continue her predatorial habits while utilizing her intelligence to increase her ability to hunt.

Part 1, Chapter 4: Allegiance

Unfortunately, this, in turn, makes her into a psychopathic murderer. “‘Hehehehe, I never felt so alive when I was hunting. I was more upfront, dim, and illogical when I preyed on a creature. But now, in this body, with this mind, and this new emotional passion, I can think through my methods of killing. I can think of the most perfect ambushes, methods to slaughter, and better ways to strip the flesh of my victims. I don’t want to choose between our two kinds, beloved, I want to be both. I want to be an intelligent predator!’ (Ch. 5). This twisted passion drastically differs from Tex’s ability to accept the changes of the world, unlike Kireina who refuses to change at all, but knows she can utilize what she’s been given since she can’t become a feral again or go back to her original time.

Tex and Kireina’s choices made them incredibly different, but showcase the positives and negatives a feral-turned-anthropomorphic creature can go through. Both characters represent what happens when human influence and domestication can do to an animal if they get in touch with too much power that can either make them comply or take charge of their fate. “Other primary concepts might include the question of anthropomorphism, the history of human perceptions of animals, the reception of evolutionary theory, or pressing contemporary issues of our age such as biomedicine, climate change, zoos, species extinction, conservation, the animal industrial complex and biopolitical power” (McDonell 7). But even though Tex changed for the better, it still didn’t change the fact that he still depended on Emily’s help and human assistance to shape who he was without giving him a chance to think about those decisions himself.

A human’s influence over animals can be domineering if their presence shapes the animal’s way of thinking. It makes us question if the way a person portrays an animal’s personality is a direct form of anthropomorphizing or domestication. “However, analyzing the literature with a different perspective it emerges that not rarely are human-animal relationships characterized by different forms and levels of discomfort and suffering for animals and, in some cases, also for people” (Prato-Previde 1). In Dinosaur Creek’s case, Emily influences most of Tex by teaching him how the world works, what one needs to do in bad situations, and how to live freely like a human would. She also helps Tex see that his time with Kireina isn’t perfect and toxic due to Kireina desiring more from Tex.

“‘Back then, it was always my responsibility to make sure the female partner I chose was always happy. As mates, we would have eggs together at one point. So as that mate who was dedicating my life to hers and our future offspring, it was my responsibility to get everything she needed and make sure she stayed by my side no matter what so we could pass both our genes into the next generation. If I didn’t do that, then my biggest concern was that she would believe I was not good enough and she would leave me’ (Ch. 10). This way of thinking left Tex to believe that his purpose was to always do what was best for his partner and expected little in return.

Tex came into the new timeline thinking he and Kireina could plan their future there, including a chance to start a family. But after she betrays him, he is left unsure about what to do now. No mate means he has no one to love and support. No concrete personality or interest means he doesn’t know what he wants to do with his life, and no full understanding of how the world works means he has no sense of how to navigate it on his own. He has plenty of friends to support him, but putting their needs before his own has left him empty and unsure about who he wants to be.

“‘Before at Terrarium, I could have done all those new things with Kireina and maybe raised that family here. But now she’s gone and I’m so much smarter and mature for this world unlike before. Yet, it’s hard for me to let go of so many years of isolation and do the same thing over and over again. Now I can’t do that and…I guess seeing so many things change and take a turn for me made me realize…’ Tex explained this in a regretful and worried voice and he looked down at his soup bowl, seeing his reflection. ‘…I don’t know what I want to do with my life.’” (Ch. 10).

While he adapts fine throughout the remainder of Part 1, it isn’t until Part 2 that his worst fears are brought to life. He spends the book figuring out how to approach his newfound feelings for Emily while grabbling with the fears of their species boundaries attracting negative attention from others. His species’ inferiority is challenged when former Terrarium prisoner Alton the spinosaurus shows up and challenges his role as leader of his rebellion, as well as his title of King of the Dinosaurs and his popularity over the humans. But the worst of it is when Kireina interrogates him and makes him think hard about whether he’s a good leader and if he found the personality to be well at it. “The entire time he was in this timeline, he was worried about what he was going to do with his life now that Kireina was not with him. But since he spent a lot of time bonding with Emily and taking up her species’ customs, he never figured out what he wanted to do for himself. He still hadn’t found any interests that he wanted to engage in, nor did he make plans for his future” (Ch. 20). He tried hard, but there were a lot of empty holes that left him unsure of who he was.

Part 2, Chapter 20: Broken Emotions

Tex’s past as well makes him struggle. “He crushed the necks of triceratops so tightly to the point of suffocation. He ripped the heads of ornithomimids and even flipped and ripped out numerous old ankylosaurs who were too sick and old to fight back with their clubs. As a feral, he was just as murderous as her with his past of kills. But even though bloodshed gave her joy, it only gave him fear and deep regret” (Ch. 20). Plus, his mutation gave him a strong figure, making him appear as a muscular soldier ready to snap a person to death in a matter of seconds. Given how he out-strengthed his friends, especially Emily who was shorter, thinner, and easier to strike down, his worst fear was that his predatory instincts would rise and unleash them on those he loved. After all, “He was a T.rex. He was a predator, a predator who had killed innocents in the past to satisfy his hunger. He tried so hard to move on from that life since he was in this timeline where he could reinvent himself into someone new. However, no matter how hard he tried, he could not let his past go” (Ch. 20).

But that doesn’t mean he’s unable to grow and move on. Tex is in a position where he can learn from others and take the time needed to hoan in on these personality traits. “The research findings on human-animal interaction span biological, psychological, and social levels of analysis, which suggests the use of the biopsychosocial model as a theoretical framework (Serpell et al., 2017), potentially augmented by more specific theories depending on the domain, animal, person, and situation” (Hansen 143). Tex utilizes his environment and allies around him to help build who he is. His time with Emily helps him learn how to navigate the world. Plus, his paleoid friends help him learn how to be a good dinosaur and rely on both his feral and anthropomorphic traits to good use.

While Tex’s character in adapting to anthropomorphism is an important part of his character, other characters have similar feelings but adapt differently. Caren the ankylosaurus arrives in the 21st century at the same time as Tex but adapts quicker and establishes her personality faster than other characters. Shane the stegosaurus is 20 years old and has been there since he was 14, using that time to flesh out his character while exhibiting characteristics that make him struggle, such as proving his species can be intelligent. Finally, Blaster, the pteranodon stands out from others because he was born into the 21st century as a paleoid, being mutated as an egg and hatching within a large family, with both parents and six other siblings. Growing up in the 21st century in a large family, he exhibits traits that make him act as a fully fleshed-out person who grew up with full human-like traits, such as access to all his emotions and gaining an extroverted personality. “Insightfully, the authors frame the agriculture revolution as a massive fusion of energy into the human system, which when coupled with the evolutionary domestication of plants and animals, created the synergy that enabled planetary dominance” (Sage 303). Blaster is a representation of a paleoid who grew up in complete human domestication, but as his character hasn’t been fleshed out yet in the first two books, he has yet to be fully discussed.

Dinosaur Creek showcases how characters like Tex struggle to adapt to a human lifestyle despite being used to living like a feral animal. Domestication and anthropomorphizing animals are taken seriously as the story showcases the psychological effects of prehistoric animals in the 21st century. While some adapt fine like Tex and his friends, characters like Kireina represent the negative effects of the process, which extend to murder and bloodshed. While it may be hard to decipher the full truth in reality, one can only speculate what these ancient animals can go through if put under difficult circumstances. “‘Science can only tell us so much about dinosaurs through the bones. But they can never truly tell us what they went through in their hearts’ Revit softly spoke out” (Ch. 10).

*Part 3 will be released sometime this year*

Works Cited

McDonell, Jenifer. “Literary Studies, the Animal Turn, and the Academy.” Social Alternatives vol. 32 no. 4, 2013, 30 April, 2023. Topic: Prep and Posts, 4/18 (plymouth.edu)

Hansen, Tia G. B., and Chalotte Glintborg. “Considering Animals in Rehabilitation Psychology.” Humanistic Psychologist, vol. 51, no. 2, June 2023, pp. 142–49. EBSCOhost, https://doi-org.libproxy.plymouth.edu/10.1037/hum0000263.

Howell, Sara. “Dinosaur Creek (Part 1).” Wattpad, 30 May 2021,

www.wattpad.com/story/271736535-dinosaur-creek-part-1.

Howell, Sara. “Dinosaur Creek (Part 2).” Wattpad, 5 June 2022,

www.wattpad.com/story/312579559-dinosaur-creek-part-2.

Prato-Previde, Emanuela, et al. “The Complexity of the Human–Animal Bond: Empathy, Attachme,nt and Anthropomorphism in Human–Animal Relationships and Animal Hoarding.” Animals (2076-2615), vol. 12, no. 20, Oct. 2022, p. N.PAG. EBSCOhost, https://doi-org.libproxy.plymouth.edu/10.3390/ani12202835.

Sage, Rowan. “The Human Planet: How We Created the Anthropocene.” Quarterly Review of Biology, vol. 94, no. 3, Sept. 2019, pp. 303–04. EBSCOhost, https://doi-org.libproxy.plymouth.edu/10.1086/705073.