There is a problem in New Hampshire schools that we are facing. According to UNH’s survey on disability status, ⅛ individuals in New Hampshire report living with a disability. While this is lower than the national average, along with a higher amount of disabled NH residents with higher education degrees, private healthcare, less poverty, and higher employment, these factors can contribute to the average income of New Hampshire which leads to a higher amount of disposable income for these residents (“New Hampshire Disability Statistics.”). This, in many cases, should lead to better public school services for individuals with disabilities, but that is where it goes astray. Of course, each New Hampshire county will differ based on property tax and the income of each resident, in the case of ConVal School District in southwestern New Hampshire, the state failed to give the district proper funding per student. $3606 was the baseline per student, while around $19,000 was allegedly needed per student to include transportation, facilities, and teacher salaries. This case won in 2021 when a judge declared the state’s lack of funding unconstitutional, which delves into the question: what about the students who aren’t considered in cases like these, who need extra support from teacher aids, for their own education and well-being? (“A Judge Says NH Needs to Change How It Funds Public Schools — Again. Now What?”). There has been an extreme lack of focus on disabled students, particularly those with ASD, by the New Hampshire public school system. There’s a drastic need to refocus our efforts on disability advocacy to show what happens in our school systems.

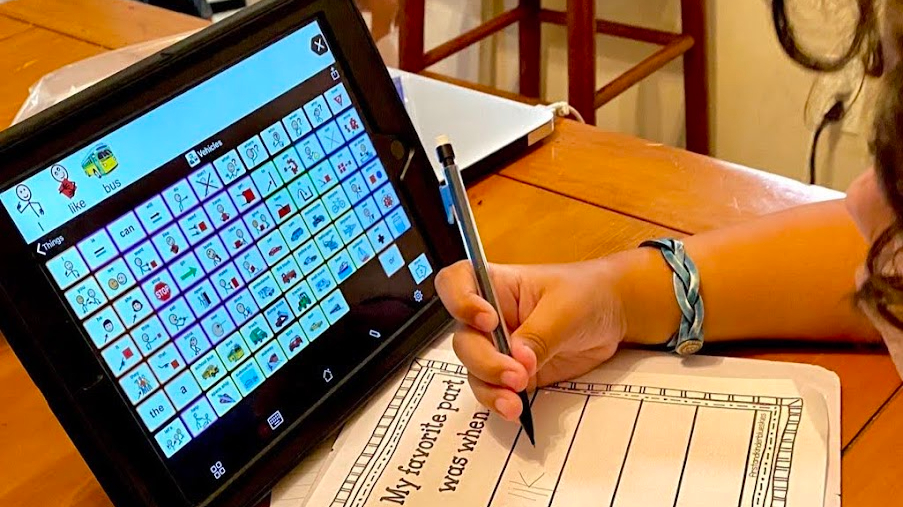

November 2006 is a big year in culture. Shakira wins record of the year, Happy Feet comes out, and my youngest brother is born. Last of five children is quite the feat to have, but my parents didn’t expect the diagnosis they were given of him never being able to talk, which he fought against and still is now. And so, I grew up around bulky communication tablets, random women coming in and out of my house to talk to my brother, long road trips in a mini-van, and a vague idea of what autism is. There’s this deep feeling of needing to protect your brother, who is apparently so different from the rest of the students and everyone’s family didn’t have a brother like mine.

They didn’t have to stick up for someone for being different or explain why your younger brother at the age of seventeen loves DVDs and Dora, but the biggest hurdle was the sheer lack of support for even autistic youth in New Hampshire. Loving someone who was a part of this ⅛ statistic and navigating who can help you, especially from the perspective of two young parents, a husband still trying to establish citizenship, and having four other children from the ages of five to seventeen. There’s this core childhood memory that feels somewhat haunting to think of in the context of what my family knows now. In 2012, there was this “March for Autism” event hosted by a local Concord organization. From a couple of back-and-forth texts from my mother, we discovered that it was Autism Speaks as of 2024. And I still have the shirt sitting on the back of my dresser, proclaiming “Someone with Autism loves me.” There’s this deep feeling of regret for my family supporting and walking for an organization that had such a deep hatred for someone I cared for so deeply.

It’s clear that there’s a problem with the clarity of how these organizations present themselves. Autism Speaks says they’re a champion for autism, yet uses applied behavioral analysis, something that is understandably hated by autistic individuals, while also being supported by Autism Speaks as a “great practice”. There are so many complications I saw my parents go through managing doctors’ appointments in Boston, finding proper schooling, finding proper care, and finding everything on their own as two nurses going through school and getting their degree. We started in the same school district as my brother throughout all of elementary school, then split off when he entered middle school because of the terrible support network that they had at the school. His para, who I only knew as Ms. B, still stayed in contact with my family, and even babysat my brother during a family graduation, but, because of how awful the school was with support for neurodivergent individuals, couldn’t follow him to middle school.

“The school placement of autistic students and disabled students is generally based on an evaluation of their needs and how they compare to the needs of nondisabled students. These needs are then accommodated in the existing school designs. This raises the question of why there are not more schools designed specifically for autistic students that break the norm of bending the existing school framework into one for autistic students.”

This is a quote from Erin Olson in her master’s thesis on the treatment of autistic individuals in public schools. Later, the paper details instances of bullying towards autistic students, a feeling of not belonging to the school, and this overall justified negativity around these institutions. (Olson, 2023). The hop from school to school, rejection to rejection based on my brother’s needs led us to a school in Wilmington, Massachusetts, around forty minutes from our home. This call we got in 2019 felt like the end of everything. An “incident” that happened in the school, a call home, a video of classroom footage of a security officer saying this fourteen-year-old was a danger to himself and others while laying on my brother’s back while he was prone on the floor. This pulled away all his resources, his paraprofessionals that came to our home, the schooling that he needed that we couldn’t trust, this harsh jump in his routine that was once wake up, go to school, come home, visit a therapist and go to bed became this unknown jumble of schedules and trying to find people who would accept this 2:1 paraprofessional to student ratio this school declared was necessary for him, simply based on him resisting restraint. This new fight pushed my parents to move to Massachusetts for more care for him as he would eventually age out of the system.

The solution to such a big issue of care is complex, and the resolution of “move to Massachusetts” shouldn’t be one of them. While not available for all families, there’s no real “best” state for autism care. We extended almost every resource in the state of New Hampshire, with this steep learning curve at each turn, with complex research, finding who supports what, and seeing who will help you. I want to say the solution is simple, that there is this “one-size-fits-all” approach to autism care, but there truly isn’t. Moving to Massachusetts wasn’t giving up nor losing a battle, but hope for another solution across the border after so many phone calls, so many parent-teacher meetings, so many “incidents” and “unregulated behavior” and hurdles and yeses and nos my parents faced in the state until they declared that yes, while they are moving, they’ll still fight for him. I want to give good examples of teacher training and student-to-student relationships with autistic individuals, but it is hard to find any out there that really are for autistic individuals, and not just suppressing them. TEACCH, the most popular teacher education program for autistic students, is backed by Autism Speaks, and teaches an individual that their behaviors are wrong, putting a bandaid solution onto their care and trying to force them to be neurotypical.

There’s one solution I like, however, and one that has stuck with me in many parts of my life. I have spent my whole life as some sort of advocate for myself or my loved ones, in the form of long talks over the breakfast table dissecting my identity into manageable chunks, or phone conversations about a shared lived experience going on for hours and hours. This need for community is the strongest human instinct, in my opinion. In the times we live in right now, where fundamental rights are up in the air, and I don’t know if this country will be safe to live in by next winter, I remind myself of the people who built me up, the ones who I sat having long and awkward dinner conversations with, or even those who hurled slurs at me from across the gas station parking lot. There’s this notion in the LGBTQ+ community that violence correlates strongly with how well they know someone, that someone being an LGBTQ+ person in their inner circle that they care about. The truth is, I wouldn’t know about all the hurdles that my brother had to go through just to get a decent public education, but my loved ones wouldn’t know about the laws coming forward to limit my rights in the state we live in if I wasn’t in their lives either. My solution is no major social change, it isn’t taking down the evil systems or toppling governments, but it’s to share one’s lived experience and listen, to build a community we all long for.