In the contemporary era of having constant access to an ever-evolving canon of literary works, there is skepticism over what to spend time reading or watching, and often, for good reason. In the case of Shakespeare, much of his work is blatantly discriminatory and relies heavily on stereotypes and bias to develop characters or forward plot; this is especially true in the case of his play, “Othello”. Known as one of his supposed “greatest works”, this play is often referenced in modern popular culture, and has undergone many adaptations, retellings, or simply traditional stagings. Presently, this play is recognized as being inherently built on racist and sexist premises, and is often criticized when reproduced as written. These claims are valid; there is virtually no argument that suggests Shakespeare’s “Othello” is spared from criticism. However, the play remains in literary circles and cultural references, and this begs the obvious question. How can such a universally-recognized abhorrent work continue to be discussed and relevant? The answer can be found in exploring the value in criticizing, adapting, and for Black artists, reclaiming the play. The simultaneous implications and the contributions of various adaptations create a fascinating framework of reforming literary criticism. By expanding discussions of the play from Shakespeare’s original work to criticism and analysis of other interpretations and artworks, the canon will transform into a far more open, inclusive, and worthwhile pursuit of knowledge about human nature than what was available in 1604.

In order to discuss the implications of “Othello” adaptations, understanding the ways in which the Shakespeare original itself was written problematically is inevitably essential. For this reason, as a work to be criticized and examined, the original play is worthy of being discussed in classrooms. In Amanda Johnson’s, a graduate student of English at Vanderbilt University, critical analysis of Othello titled “Reading What Isn’t There: Empiricism, Delusion, and the, Construction of Race and Racism in Othello”, the critic delves into an analysis of Othello’s sense of self as tied to his race and how Iago’s deceit undermines this through his deceit. In a scene where Othello is trying to justify in his own mind how Desdemona could be allegedly having an affair he says, “Haply for I am black, And have not the parts of conversation,” (Othello III.iii.265-270). Othello is attempting to explain to himself that, because he is black, this implies that he is less eloquent than Cassio, who is white, and therefore, cannot hold Desdemona’s love. In the critical analysis, Johnson states, “The second line of the passage, with its conjunction ‘and’ suggests either a causal or concomitant relationship between his blackness and his lack of eloquence,” (22, Johnson). This asserts an underlying self-hatred that comes out of internalized racism that was likely present prior to Iago’s plot, but was being projected as a need to prove himself as “different” from others, and therefore worthy of respect. Othello is filled with instances of perpetuated stereotypes and leaves an audience with a Black character who is irredeemable and is blamed for a system that he did not create. Instead of continuing to allow a canon that reveres texts that rely on dangerous tropes and sinister messages, instead, uplift Black artists who reclaim Othello through their own original work.

With centuries of stage productions and decades of film adaptations of “Othello” directed or performed by primarily White artists without much intention or regard for the racial implications of the play, Liz White, an independent filmmaker, directed an adaptation in 1962-1966 that strayed from this pattern. With an all-Black cast that developed from a theater production of the play in1960, White created a unique and fresh take on the play. In Peter Donaldson’s journal article on the film in Shakespeare Quarterly, he states

“Because Othello is close, ethnically, to the cast without really being one of them, the eruption of mistrust and rage is especially poignant; in rejecting Othello, the “Venetians” are rejecting a part of themselves,” (485, Donaldson).

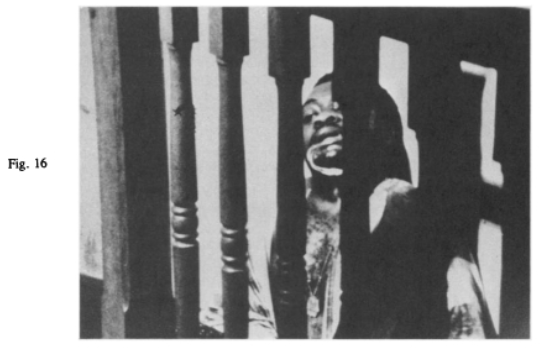

By choosing to incorporate a completely Black cast, Liz White is able to transform dynamics between characters of the play and the commentary of those dynamics into her own. As Donaldson explains, the Venetians’ hatred for Othello, including Iago’s feelings towards Othello, change from manipulation of racist stereotypes for an agenda to a much deeper yet more subtle internalized racism. The Venetians are afraid of their own selves being recognized as Black and fear Othello’s unapologetic strong sense of himself and ownership of his own body and of his Blackness. This pride makes his descent into outrage, and eventually his murder of Desdemona, even more tragic, but affords him a more meaningful realization of his own actions than present in the original play. His epileptic seizures, as presented by White’s vision, are exceptionally visceral in the film. “His personal suffering becomes a visual allusion to the chaining and confinement of slaves,” (Donaldson, 494).

In this scene, Othello violently seizes while biting down on a gold chain in an attempt to restrain himself, and the presentation of this graphic image lends to a commentary on slavery. Not only does this emphasize the ways in which Othello is victimized due to his disability, but also presents a much larger plot within the original story that through her creative storytelling, Liz White extricates and brings to the forefront.

In Liz White’s film adaptation of “Othello”, she makes several directorial moves to create a more sympathetic version of Iago than is present in the original text. Iago, however, does not become more likable or any less racist in the film. The audience simply comes to understand his motivation better. In the first scene of the film, Iago is carrying Othello’s bags, and Othello is unaware of Iago’s resentment of being passed over for the promotion. “The passing over of Iago in this version is a crucial failure of sensitivity, a blind spot in the relations between a confident African and his Black American companion and subordinate,” (486, Donaldson). While this is the same scenario presented in the play, White’s additions to the play, regarding Othello’s traditional African cultural ties, and Iago’s lighter-skinned American blackness creates an additional layer of complexity. White’s ability to explain Iago’s motivations without creating sympathy for a villan who manipulates racist and sexist tropes to achieve revenge is a prime example of how to reimagine Iago’s character, especially from the perspective of the character as a Black actor, in a meaningful way. In recent works, other authors have attempted to replicate this reimagining of Iago’s character, and with some, this creates the exact same set of problematic questions raised by the original play. In Nicole Galland’s novel, “I, Iago”, published in 2012, the work acts as a prequel and a subsequent re-telling of the original play. This novel characterizes Iago prior to meeting Othello and even tells the love story of Emilia and Iago prior to the play picking up with the original events of the play. While Galland succeeds in creating a historically accurate and buyable background for Iago, she fails to acknowledge the racism present in Iago’s character and behavior. In the final scenes when Othello kills Desdemona, Iago, in Galland’s work, is shocked evidently because he never anticipated a “civilized Venetian to commit such a crime”, which heavily implicates a racial undertone that is never addressed by Galland. In a review in the American Shakespeare Center, a reviewer states, “Iago freely admits that he wants.. To remove Desdemona from the picture (though he does not intend to do so through her death),” (ASC). By making this leap in Iago’s expectations, Galland unintentionally implies that Iago’s racism is justified because he was betrayed deeply by Othello, and proves what could be problematic in attempts to create interpretations of a play that ignore the original racialized intent of the play itself. In order to fully reclaim and redevelop a problematic play, the problems must be examined and addressed, before being transformed into an artistic interpretation, and when pairing texts to read in place of the original play, this choice is significant.

Beyond just retellings and adaptations, artists have been creating entirely new works out of the remnants of Shakespeare’s problematic work. In Keith Hamilton Cobbs’, “American Moor”, he creates a refreshing and unique work that is largely the internal monologue of an actor auditioning for the role of Othello. The actor is a Black man auditioning for the role under a white director and expresses through his monologues commentary on the play and society as a whole. In one scene, the actor is explaining his frustration with both the director’s comments on how to improve his portrayal of Othello, but also the theater industry at-large that attempts to impose assumptions of knowledge based on an education, rather than the lived experiences of Black actors. “Purely by virtue of being born Black in America, I know more about who this dude is than any graduate program could ever teach you,” (Page 24, Cobb). The actor is expressing, both internally towards the director and to the audience, that undermining the actual experiences of BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and people of color) actors portraying BIPOC characters and that is exactly what happens so often in Othello productions. There is even comedic irony here employed by Cobb throughout much of this scene in that the scene being criticized by the director of the original play is about Othello proving himself to the Venetian court worthy of marrying Desdemona, a white woman. The actor is having to suppress his true feelings and perform a portrayal of a Black man that is inaccurate to his own lived experiences as a Black man. Cobb’s ability to use his artistry to reclaim Othello as a play that belongs to the Black community to define and recreate as creators see fit is worthy of praise and use in classrooms as a staple of how Shakespeare’s work can be used to advance, rather than restrict, creative freedom.

In examining threads between the reasons that literary canons develop, the common connections that bind these enduring texts together are the universal questions that the works force us to reckon with. Shakespeare’s “Othello” is rife with problematic questions and assumptions to be challenged that give an explanation for the standard use of the play in classrooms and in the canon of classic literature, but these questions are not exclusive to the play itself, and are even more worthy of asking through the work of adaptations and creative avenues. Through the work of Black artists, critics, and playwrights, “Othello” can be adapted and reimagined as a work that can provide answers to the questions that the original play asked. This framework of pairing criticisms, contemporary re-imaginings, and films with outdated and harmful works in studying the literary canon will provide a more inclusive and open space for students and all readers to ask and answer questions that will shape the way that we view the world and literary space.

Works Cited

American Shakespeare Center. “Book Review: I, Iago, by Nicole Galland.” American Shakespeare Center, 18 May 2012, https://americanshakespearecenter.com/2012/05/book-review-i-iago-by-nicole-galland/.

Cobb, Keith Hamilton, and Kim F. Hall. American Moor. Methuen Drama, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020.

Donaldson, Peter. “Liz White’s ‘Othello.’” Shakespeare Quarterly, vol. 38, no. 4, 1987, pp. 482–95. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2870428. Accessed 12 Dec. 2022.

Johnson, Amanda Louise. “Reading What Isn’t There: Empiricism, Delusion, and the Construction of Race and Racism in Othello.” Vanderbilt University, Vanderbilt University, Aug. 2009, https://ir.vanderbilt.edu/bitstream/handle/1803/13527/amandajohnson.pdf?sequence=1.

Shakespeare, William. Othello from The Folger Shakespeare. Ed. Barbara Mowat, Paul Werstine, Michael Poston, and Rebecca Niles. Folger Shakespeare Library, December 12, 2022.